Drag Racing with Bloom Filters

Wherein, I present a ridiculous approach to solving Task 5 of the NSA's 2025 Codebreaker Challenge.

January 15, 2026

Meet The Bad Guys

Task 5 of this year's Codebreaker Challenge from the National Security Agency asked us to decrypt traffic headed towards a threat actor's command and control server. In Task 4, we unpacked the attacker's malware to get a peek at the protocol they used, and the messages we needed to decrypt were located in the packet capture we were given as part of Task 2.

To keep it brief, here's a relevant sample of pseudocode from the malware we were given. (aes_encrypt is a simple wrapper around OpenSSL's EVP API)

Flawed Key Generation Algorithm

uint64_t generate_key(uint8_t* outBuf, uint32_t length) {

if (length != 32)

return -1;

int64_t result[4] = { 0 };

int64_t md[4] = { 0 };

const char hmacKey[11] = "ABCD123321";

FILE* fp = fopen("/dev/random", "r");

if (!fp)

return -1;

if (fread(outBuf, 1, 32, fp) != 32) {

fclose(fp);

return -1;

}

fclose(fp);

HMAC(EVP_sha3_256(), hmacKey, sizeof(hmacKey), outBuf, 32, md, 0);

outBuf[0] = result[0] = (outBuf[2] ^ md[2]) >> 38;

outBuf[1] = result[1];

outBuf[2] = result[2];

outBuf[3] = result[3];

return 0;

}

Some of you may hold the opinion that 26 bits of entropy in your key is suboptimal for most use cases.

Fitting into the wider context, however, we see that generate_key is actually used twice:

the bad guys used a custom homebrew double-AES built on top of the raw block cipher, rather than a well-established mode

like Counter or Cipher Block Chaining.

Encryption Routine

void custom_enc(void* aes1, void* aes2, char* input, int32_t length, int64_t out, int64_t outLength) {

// allocate a temporary buffer for the first aes ciphertext

int32_t tempLength = length + 16;

void* tempOut = malloc(length + 16);

// double-aes encrypt, first with aes1 and then with aes2, to create our ciphertext

aes_encrypt(aes1, input, length, tempOut, &tempLength);

aes_encrypt(aes2, tempOut, tempLength, out, outLength);

free(tempOut);

}

The bad guys also ensured we had a known plaintext: the first packet sent over the encrypted wire was a 13 byte string, which would be padded with 3 bytes to form the plaintext of the first block. As I first dipped my toes into this task, I began working out how to run a brute-force on the key using the known plaintext, but before I could finish, I noticed something a little fishy.

Sidequest: The Padding Cheese

Looking into the packet captures, there's a pattern that stands out almost immediately: the ciphertexts are always one block larger than the plaintext, and the last block is always the same. This is due to the behavior of padding in block ciphers, like AES: they only work on blocks of specific sizes (hence the name "block cipher"). For AES, this is a block of 16 bytes, or 128 bits, regardless of the key size, so if a plaintext isn't exactly a block size, then we need to add extra bytes to make it fit.

One of the many ways to go about padding is what's referred to as PKCS#7 padding. If our plaintext is 3 bytes short of a block, then we append 3 bytes of the value '3' to our plaintext, as seen below in the first block. If our plaintext is 5 bytes short of a block, then we append 5 bytes of the value '5', etc. The decryptor can take the very last byte, check that the padding is correct (eg, if the last byte is '6', that the end of the block is indeed '6' repeated 6 times), and then return the exact (plaintext, length) pair that was passed in on the encryptor's end.

This is all well and good, but when our plaintext lines up to be exactly a block, then we instead need to append 16 bytes of the value '16', just to ensure the decryptor gets the memo.

Captured Traffic

#1: REQCONN packet

13 52 67 d5 b6 1a f4 b7 c5 b0 79 dc 8b cc 59 62

ea e5 dc bd 69 5d 3e 24 5b e5 09 13 bf 64 37 53

(known plaintext)

de c0 de c0 ff ee 82 69 81 67 79 78 78 03 03 03

#2: REQCONN_OK packet

6a 45 49 9c 4c 90 95 44 dc 36 93 99 be ee 5e 49

84 29 6e 05 a9 9d d4 f5 8c 89 f1 c6 36 48 26 ba

ea e5 dc bd 69 5d 3e 24 5b e5 09 13 bf 64 37 53

(known plaintext)

de c0 de c0 ff ee 82 69 81 67 79 78 78 95 79 75

16 16 16 16 16 16 16 16 16 16 16 16 16 16 16 16

Now, this task was supposed to be a meet in the middle attack (according to the NSA, at least),

but the padding lets us quickly find the first encryption key. Because the output of AES is always a multiple of 16, every plaintext encrypted by the second call to aes_encrypt will always have the same 16 bytes of padding appended to it. This means we can just do a simple brute

force on the last block, hunting for a key that decrypts to a plaintext of 16 16's. This is pretty simple,

and the program to do it runs in under a second:

Brute Force

Block desired = { .u8 { 0xea, 0xe5, 0xdc, 0xbd, 0x69, 0x5d, 0x3e, 0x24, 0x5b, 0xe5, 0x09, 0x13, 0xbf, 0x64, 0x37, 0x53 } };

for (uint32_t i = 0; i < 67108864; ++i) {

Block key = { .u32 { i, 0, 0, 0 } };

Block block = { .u8 { 16, 16, 16, 16, 16, 16, 16, 16, 16, 16, 16, 16, 16, 16, 16, 16 } };

Cipher::Aes( key.u8 ).encrypt_block( block.u8 );

if (block.u128 == desired.u128) {

std::cout << "Found First:" << i << std::endl;

}

}

Of course, decrypting our ciphertext with the first key we found for this method gives us another simple brute force, again with only 67108864 possible keys. With both keys under our belt, we're able to decrypt the entire conversation, and learn some juicy badguy secrets along the way.

Back in the world of the blogpost, however, we're going to forget to spread the padding cheese over our solution crackers. Assuming the creators disabled padding on

the second aes_encrypt operation, and we had to do a meet in the middle... what's the fastest way to go about it?

Trading Time for Space

A meet-in-the-middle attack is a way in which we can trade off time for space, in the

midst of some computation, by performing the computation half way from one side and half way from another.

For example, there are 252 key pairs to brute force, despite there being only 226 keys possible for each application of AES.

Instead of running aes_encrypt on our plaintext 252 times, how about we run aes_decrypt on the ciphertext 226 times,

store all of the results, and check which invocation of aes_encrypt spits out something equal to one of our aes_decrypt runs?

This is a meet-in-the-middle attack, and it's one of the many ways you can speed up attacks on invertible functions. AES is invertible knowing the key, so ENCk(DECk(pt)) = DECk(ENCk(pt)). Therefore, we can rearrange ct = ENCk1(ENCk2(pt)), as mk1 = DECk1(ct) and mk2 = ENCk2(pt). When mk1 = mk2, we have found k1 and k2. Now we have 226 instances of mk1 to check against another 226 instances of mk2, much more manageable than the 252 (k1, k2) pairs we had to wrangle before.

Trading space for time lets us wrangle a large complexity into one several orders of magnitude lower. However, we still need to store 226 (a little over 67 million) m values. This is not a trivial task.

My first foray into this was a C++ ordered set (a red-black tree), which was not a good idea. The full thing took several gigabytes and the program took about two minutes just to run the forward pass. I'd thought it'd be bad, but this was a whole other level of stink. Everything was bad: the allocator couldn't handle the load even with mimalloc bolted on, the tree structure thrashed the cache to no end, and the branches put the processor into a practically idle state. I'd improve the performance a little by working out all the pressure points, but ultimately these general-purpose containers aren't designed for membership queries over sets this large. If I wanted something done right I'd have to do it myself.

Bloom Filters & Approximate Membership Queries

An approximate membership query is an acceleration structure over a set that, given an item, spits out one of two responses: "Absolutely Not!", a definite rejection that confirms the item is not in a set, and "Mayhaps...", which tells you that the item might be in the set, but there's truly no way of knowing.

There's many ways of going about making an approximate membership query. Probably the most famous example is simply hashing the input and truncating the hash, which is literally just a hashmap. That is, hashing a key yields a bucket, which may or may not contain the key/value pair, but the key/value pair will Absolutely Not be in any of the other buckets.

Approximate Membership Queries have many names, and I think my favorite is simply calling it a "fast-reject", because that's all it is: quickly reject as many possible solutions as we can with a simple trivial check, before performing more expensive computations to confirm the remaining cases.

Bloom filters are a form of Approximate Membership Query that is essentially a "fast-reject" over a set of items, using an arena of bits. To make a bloom filter, we need a hash function: given an item, we need to spit out a number, where putting in the same item multiple times will always spit out the same number. To add an item to the set, we simply hash the item to find it's number, and then set that bit number in the arena to 1.

If you've ever played with those shape sorter toys as a kid ("it goes in the square hole..."), then this essentially like that. Every time we add an item, we bore out the hole a little bit so that the item fits. Of course, if we bore too many holes, then everything will fit; but there is no way we have bored a hole for something previously if it doesn't fit.

With that in mind, imagine the big list of bits as a hole, and each item's hash determining which pieces of the hole we need to bore. To bore out the hole and expand it for our item, we simply set those bits in the hole to 1. Of course, like holes in real life, once you've cut them out, they are rather difficult to put back together again. If you arbitrarily set bits to 0, then you'd be putting blockages in arbitrary parts of the hole, causing random pieces that we previously added to suddenly not fit.

Lastly, we can choose the shape of each item that we wish to bore using whatever method we'd like. Typically, bloom filters assign 4-20 numbers to each item by putting the same item through multiple different hash functions. And, of course, the more items we add (and thus the bigger the hole gets), the more items will have false-mayhaps-es.

Coincidentally, the NSA does a lot of cool research into approximate membership queries and satisfiability problems (I wonder why?), even going so far as to publish a highly space-efficient AMQ based on XOR satisfiability solvers on GitHub.

A Forward Pass to be Reckoned With

To create our bloom-filter-accelerated meet in the middle attack, we replace the cookie-cutter forward pass (which usually builds a dictionary of [ciphertext, key] pairs) with a forward pass that builds up a bloom filter containing every ciphertext found in the forward pass. During our backwards pass, we then check if each generated ciphertext matches in the bloom filter, and then put each match in a separate list for further scrutiny.

The downside of this approach is that we need to do another forward pass to check our new whittled-down list from the backwards pass. However, in reality, this performance hit is negligible (again, it took less than a second to brute-force all combinations with our snippet above), and the performance of the fast-reject forwards-backwards-forwards outweighs even the best forwards-backwards implementations.

Part of the reason for this is that compute power has grown far more rapidly than memory bandwidth has. Memory bandwidth is expensive, especially in hardware, which has ensured that the price-constrained consumer market has rarely, if ever, seen more than two memory channels. Trading off time for space can make sense, but sometimes, when we get a little too much space, we have to trade some of that back off for time.

Ultimately, our forwards-backwards-forwards approach shaves off over a gigabyte of memory in exchange for a few extra seconds of processing power. Worth it.

Bloom in the Bliddle

// Create a forwards bloom filter that contains all ciphertexts

// of our plaintext with all possible keys.

const BruteBloom* CreateBloomFilter() {

BruteBloom* bloom = new BruteBloom();

for (uint32_t i = 0; i < 67108864; ++i) {

Block block = { 0xde, 0xc0, 0xde, 0xc0, 0xff, 0xee, 'R', 'E', 'Q', 'C', 'O', 'N', 'N', 0x3, 0x3 ,0x3 };

Block key = { .u32 = { i, 0, 0, 0 } };

Cipher::Aes( key.u8 ).encrypt_block( block.u8 );

bloom->insert(block);

}

return bloom;

}

// Given a bloom filter of all forwards ciphertexts

// find all backwards combinations that are

// "maybe in" the set of ciphertexts, with some error

std::vector<std::pair<uint32_t, Block>> RunBackwardsBrute(const BruteBloom* filter) {

std::vector<std::pair<uint32_t, Block>> matches;

for (uint32_t i = 0; i < 67108864; ++i) {

Block block = { 0x13, 0x52, 0x67, 0xd5, 0xb6, 0x1a, 0xf4, 0xb7, 0xc5, 0xb0, 0x79, 0xdc, 0x8b, 0xcc, 0x59, 0x62 };

Block key = { .u32 = { i, 0, 0, 0 } };

Cipher::Aes( key.u8 ).decrypt_block( block.u8 )

if (filter->find(block)) [[unlikely]]

matches.emplace_back( i, block );

}

return matches;

}

// Given a set of backwards ciphertexts that were "maybe in"

// the forwards bloom set, run over all forwards combinations

// to find out which ones match.

std::pair<uint32_t, Block> RunForwardsBrute(const std::vector<std::pair<uint32_t, Block>>& matches) {

for (uint32_t i = 0; i < 67108864; ++i) {

Block block = { 0xde, 0xc0, 0xde, 0xc0, 0xff, 0xee, 'R', 'E', 'Q', 'C', 'O', 'N', 'N', 0x3, 0x3 ,0x3 };

Block key = { .u32 = { i, 0, 0, 0 } };

Cipher::Aes( key.u8 ).encrypt_block( block.u8 );

for (int j = 0; j < matches.size(); j++)

if (matches[j].second.u128 == block.u128) [[unlikely]] {

return { i, matches[j].first };

}

}

}

return { -1, -1 };

}

Not All Nice and Rosy

Bloom filters sound all nice and rosy, but stochastic data structures are tricky in more ways than one. First off, Bloom filters aren't "magical set compression functions", and they still follow entropy laws. In a broad sense, Bloom filters with N bits become useless once we store N items, but the actual probability of false positive depends on both the number of hashes we use and the size of the filter, and varies by several orders of magnitude with small tweaks. (There's actually calculators you can use to figure out the parameters, in case you were wondering)

With this in mind, I settled on a parameter set of 232 bits and 10 hashes, the parameters used in the link above. While it may sound strange to use less hashes than the ideal for that size & entry count, this program doesn't operate in a vacuum on a perfect machine where all memory accesses are nice and fast and dandy. Rather, I'd found myself reaching a point where, on my machine, each fetch to DRAM was taking much longer (by causing a ridiculous amount of pipeline stalls) than the amount of time the reduced false-positive chance saved me in other parts of my program.

Even then, 10 fetches to DRAM was too much. I ended up biasing my hash functions so that the resulting numbers clustered into one of two 64-bit words, each of which would be fetched only once per lookup. In the future I may experiment with 32-bit words, but I was also a little worried about the potential impact of a single word becoming saturated with all 1's.

Pedantically speaking, this turns one big bloom filter of N bits into N/64 bloom filters of 64 bits, and using another hash to select which two bloom filters to match a ciphertext against. But in my head this is still one big, happy bloom filter, and you can't take this from me.

Biased Hashing

// Normally this wouldn't be an acceptable hash function.

// *however* we are only putting AES blocks into the bloom

// filter, so we can piggyback off of AES's PRP status

template<>

__forceinline uint64_t hash<Block>(const Block& obj, int bias) {

return obj.u64[bias & 1] ^ (bias * 0xC2B2AE3D27D4EB4FULL);

}

// Turn a hash into a mask with N bits set.

template<int N>

__forceinline uint64_t mask(uint64_t& source) {

if constexpr (N == 1) {

return (1ull << (source & 63))

} else {

return (1ull << (source & 63)) | mask<N-1>(source >> 6);

}

}

So... Results?

At the end of my little experiment with bloom filters, I had a program that could solve task 5 on a single thread, using a bloom-accelerated meet-in-the-middle attack, in 9700ms. Multithreading it 8 ways on the forwards bloom filter generation gives a total solve time of 5700ms. I didn't attempt to multi-thread the backwards and second-forwards passes in this codebase, so there's still room for improvement.

As far as I'm aware, this is the fastest implementation for meet-in-the-middle attacks at the 252 level. Of course, there's not a lot of them out there, and it's not easy to find the really good ones in the barren lands of GitHub. However, I think even my naive little implementation here shows a lot of progress for future use in making space-time tradeoffs a good bargain.

So... That's It?

Well, not really. Since figuring out how to apply bloom filters to this task, I've been thinking about how to use the same bloom-filter technique to accelerate invisible-salamanders-style birthday attacks on counter modes of operation without key-committing MACs (eg, AES-GCM, ChaCha20-Poly1305). Ultimately, these kinds of attacks will only become more relevant as these modes become more used (and abused...), whenever the one-key assumption doesn't exactly hold up to scrutiny.

Contrary to popular belief, invisible salamanders impacts more people than facebook, and in more ways than just breaking the way reporting images works. Imagine being able to send the exact same encrypted email to two people, and having it decrypt to two different plaintexts based on which one opened it, all under the watchful gaze of an authenticated cipher. Now THAT would allow you to get up to a good amount of shenanigans. More on that in a future episode of My Blabber.

Correction: A previous version of this article incorrectly stated Filippo Valsorda's Age tool was potentially vulnerable to invisible-salamanders attacks. Age is not vulnerable as it uses HMAC over the header, despite using XChaCha20-Poly1305 on the actual file contents. However, similarly-designed file encryption tools that do not undergo the same "sanity" checks may be vulnerable, which is the point I was attempting to get across. Oops!

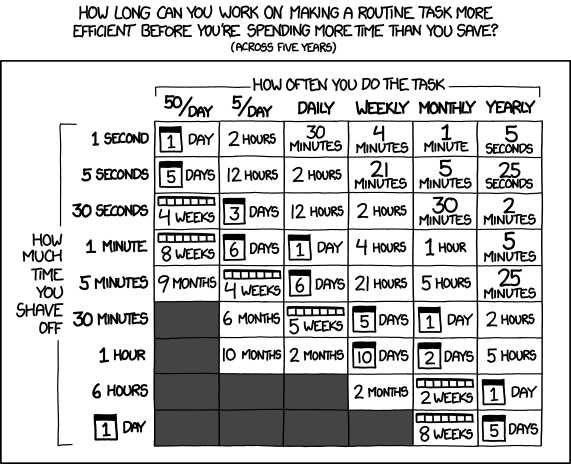

Randall Munroe's XKCD